“Programming is like kicking yourself in the face, sooner or later your nose will bleed.” - Kyle Woodbury

A computer language is described by its syntax and semantics; where syntax is about the the grammar of the language and semantics the meaning behind the sentence. And jumping into a new programming language correlates to visiting a foreign country with only that 9th grade Spanish 101 class under your belt; there is no better way to learn than to immerse yourself in the environment! Although it’ll be painful early on and your nose will surely bleed, eventually you’ll learn the dialect and the quircks that come along with it.

Throughout this website you’ll learn much of the fundamental syntax and semantics of the R programming language; and hopefully with minimal face kicking involved. However, this section serves to introduce you to many of the basics of R to get you comfortable. This includes

Download and install R, a free software environment for statistical computing and graphics from CRAN, the Comprehensive R Archive Network. It is highly recommended to install a precompiled binary distribution for your operating system; follow these instructions:

Install RStudio’s IDE (stands for integrated development environment), a powerful user interface for R. RStudio includes a text editor, so you do not have to install another stand-alone editor. Follow these instructions:

There are other R IDE’s available: Emacs, Microsoft R Open, Notepad++, etc; however, I have found RStudio to be my preferred route. When you are done installing RStudio click on the icon that looks like:

and you should get a window that looks like the following:

You are now ready to start programming!

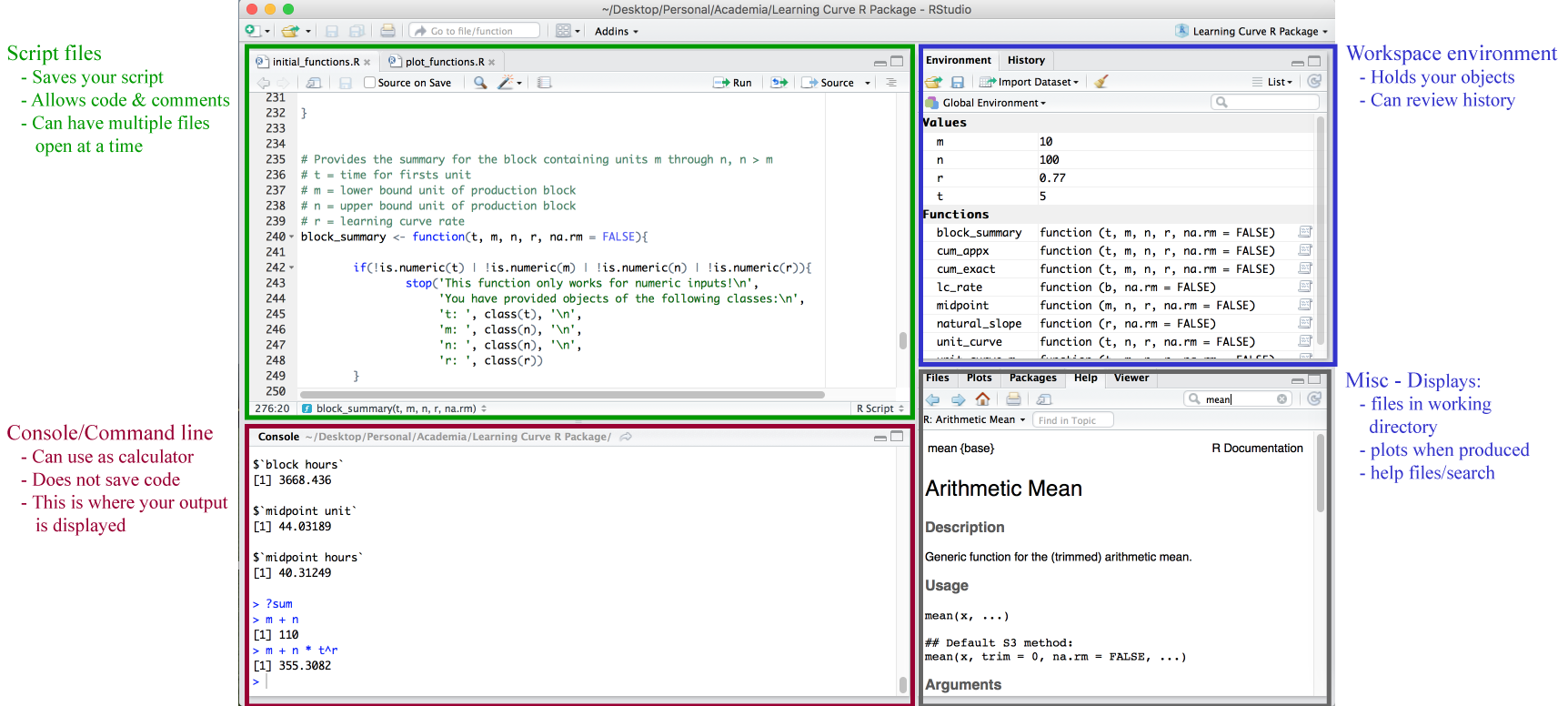

The RStudio console is where all the action happens. There are four fundamental windows in the console, each with their own purpose. I discuss each briefly below but I highly suggest this tutorial for a thorough understanding of the console.

The top left window is where your script files will display. There are multiple forms of script files but the basic one to start with is the .R file. To create a new file you use the File » New File menu. To open an existing file you use either the File » Open File… menu or the Recent Files menu to select from recently opened files. RStudio’s source editor includes a variety of productivity enhancing features including syntax highlighting, code completion, multiple-file editing, and find/replace. A good introduction to the script editor can be found here.

The script editor is a great place to put code you care about. Keep experimenting in the console, but once you have written code that works and does what you want, put it in the script editor. RStudio will automatically save the contents of the editor when you quit RStudio, and will automatically load it when you re-open. Nevertheless, it’s a good idea to save your scripts regularly and to back them up.

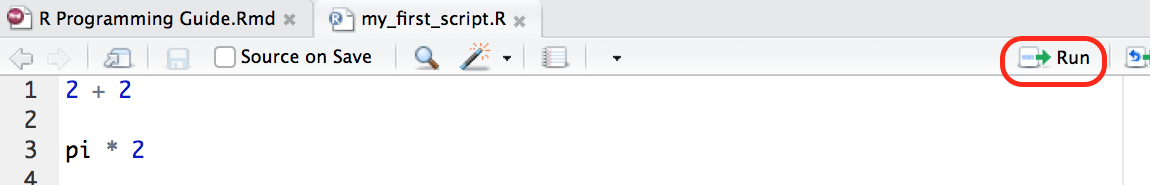

To execute the code in the script editor you have two options:

The top right window is the workspace environment which captures much of your your current R working environment and includes any user-defined objects (vectors, matrices, data frames, lists, functions). When saving your R working session, these are the components along with the script files that will be saved in your working directory, which is the default location for all file inputs and outputs. To get or set your working directory so you can direct where your files are saved:

# returns path for the current working directory

getwd()

# set the working directory to a specified directory

setwd("path/of/directory")

For example, if I call getwd() the file path “/Users/bradboehmke/Desktop/Personal/Data Wrangling” is returned. If I want to set the working directory to the “Workspace” folder within the “Data Wrangling” directory I would use setwd("Workspace"). Now if I call getwd() again it returns “/Users/bradboehmke/Desktop/Personal/Data Wrangling/Workspace”. An alternative solution is to go to the following location in your toolbar Session » Set Working Directory » Choose Directory and select the directory of choice (much easier!).

The workspace environment will also list your user defined objects such as vectors, matrices, data frames, lists, and functions. For example, if you type the following in your console:

x <- 2

y <- 3

You will now see x and y listed in your workspace environment. To identify or remove the objects (i.e. vectors, data frames, user defined functions, etc.) in your current R environment:

# list all objects

ls()

# identify if an R object with a given name is present

exists("x")

# remove defined object from the environment

rm(x)

# you can remove multiple objects

rm(x, y)

# basically removes everything in the working environment -- use with caution!

rm(list = ls())

You can also view previous commands in the workspace environment by clicking the History tab, by simply pressing the up arrow on your keyboard, or by typing into the console:

# default shows 25 most recent commands

history()

# show 100 most recent commands

history(100)

# show entire saved history

history(Inf)

The bottom left window contains the console. You can code directly in this window but it will not save your code. It is best to use this window when you are simply wanting to perform calculator type functions. This is also where your outputs will be presented when you run code in your script. Go ahead and type the following in your console:

2 * 3 + 8 / 2

The bottom right window contains multiple tabs. The Files tab allows you to see which files are available in your working directory. The Plots tab will display any plots/graphics that are produced by your code. The Packages tab will list all packages downloaded to your computer and also the ones that are loaded (more on this later). And the Help tab allows you to search for topics you need help on and will also display any help responses (more on this later as well).

There are multiple options available for you to set and customize your console. You can read about, and set, available options for the current R session with the following code. For now you don’t need to worry about making any adjustments, just know that many options do exist.

# learn about available options

help(options)

# view current option settings

options()

# change a specific option (i.e. number of digits to print on output)

options(digits=3)

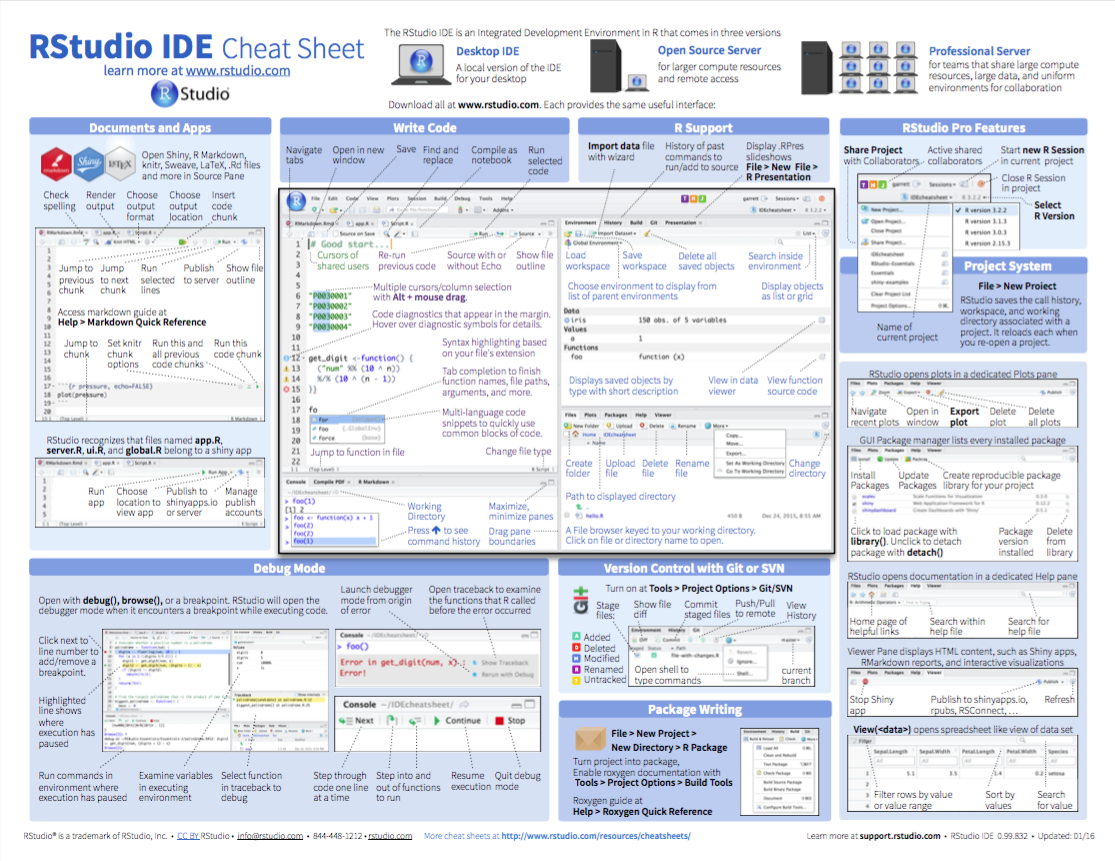

For a thorough tutorial regarding the RStudio console and how to customize different components check out this tutorial. You can also find the RStudio console cheatsheet shown below here or by going to Help menu » Cheatsheets. As with most computer programs, there are numerous keyboard shortcuts for working with the console. To access a menu displaying all the shortcuts in RStudio you can use option + shift + k. Within RStudio you can also access them in the Help menu » Keyboard Shortcuts.

pi in the console. Set the option to show 8 digits. Re-type pi in the console.?pi in the console. Note that documentation on this object pops up in the Help tab in the Misc. Display.pi in line 1 of this script, option(digits = 8) in line 2, and pi again in line three. Execute this code one line at a time and then re-execute all lines at once.The help documentation and support in R is comprehensive and easily accessible from the command line (aka the console).

To leverage general help resources you can use:

# provides general help links

help.start()

# searches the help system for documentation matching a given character string

help.search("linear regression")

Note that the help.search("some text here") function requires a character string enclosed in quotation marks. So if you are in search of time series functions in R, using help.search("time series") will pull up a healthy list of vignettes and code demonstrations that illustrate packages and functions that work with time series data.

For more direct help on functions that are installed on your computer you can use the following. Test these out in your console:

help(mean) # provides details for specific function

?mean # provides same information as help(functionname)

example(mean) # provides examples for said function

Note that the help() and ? function calls only work for functions within loaded packages. You’ll understand what this means shortly.

Typically, a problem you may be encountering is not new and others have faced, solved, and documented the same issue online. The following resources can be used to search for online help. Although, I typically just Google the problem and find answers relatively quickly.

RSiteSearch("key phrase"): searches for the key phrase in help manuals and archived mailing lists on the R Project website.stats package is a core package that comes with base R. Pull up the help documentation regarding this package.grid package there is an introductory vignette titled “grid”. Access this vignette.log function. Check out the help information on this function.In R, the fundamental unit of share-able code is the package. A package bundles together code, data, documentation, and tests and provides an easy method to share with others1. As of May 2017 there were over 10,000 packages available on CRAN, 1000 on Bioconductor, and countless more available through GitHub. This huge variety of packages is one of the reasons that R is so successful: chances are that someone has already solved a problem that you’re working on, and you can benefit from their work by downloading their package.

The most common place to get packages from is CRAN. To install packages from CRAN you use install.packages("packagename"). For instance, if you want to install the ggplot2 package, which is a very popular visualization package you would type the following in the console:

# install package from CRAN

install.packages("ggplot2")

As previously stated, packages are also available through Bioconductor and GitHub. Bioconductor provides R packages primarily for genomic data analyses and packages on GitHub are usually under development but have not gone through all the checks and balances to be loaded onto CRAN (aka download and use these packages at your discretion). You can learn how to install Bioconductor packages here and GitHub packages here.

Once the package is downloaded to your computer you can access the functions and resources provided by the package in two different ways:

# load the package to use in the current R session

library(packagename)

# use a particular function within a package without loading the package

packagename::functionname

For instance, if you want to have full access to the tidyr package you would use library(tidyr); however, if you just wanted to use the gather() function which is provided by the tidyr package without fully loading tidyr you can use tidyr::gather(...) (here ... just represents the arguments that you would include in this function).

For more direct help on packages that are installed on your computer you can use the help and vignette functions. Here we can get help on the ggplot2 package with the following:

help(package = "ggplot2") # provides details regarding contents of a package

vignette(package = "ggplot2") # list vignettes available for a specific package

vignette("ggplot2-specs") # view specific vignette

vignette() # view all vignettes on your computer

Note that some packages will have multiple vignettes. For instance vignette(package = "grid") will list the 13 vignettes available for the grid package. To access one of the specific vignettes you simply use vignette("vignettename").

There are thousands of helpful R packages for you to use, but navigating them all can be a challenge. To help you out, RStudio compiled a guide to some of the best packages for loading, manipulating, visualizing, analyzing, and reporting data. In addition, their list captures packages that specialize in spatial data, time series and financial data, increasing spead and performance, and developing your own R packages.

dplyr is an extremely popular package for common data transformation activities and is available from CRAN. Perform the following tasks:

dplyr package.dplyr package.dplyr package.dplyrThe first operator you’ll run into is the assignment operator. The assignment operator is used to assign a value. For instance we can assign the value 3 to the variable x using the <- assignment operator.

# assignment

x <- 3

Interestingly, R actually allows for five assignment operators:

# leftward assignment

x <- value

x = value

x <<- value

# rightward assignment

value -> x

value ->> x

The original assignment operator in R was <- and has continued to be the preferred among R users. The = assignment operator was added in 2001 primarily because it is the accepted assignment operator in many other languages and beginners to R coming from other languages were so prone to use it. However, R uses = to associate function arguments with values (i.e. f(x = 3) explicitly means to call function f and set the argument x to 3. Consequently, most R programmers prefer to keep = reserved for argument association and use <- for assignment.

The operators <<- is normally only used in functions which we will not get into the details. And the rightward assignment operators perform the same as their leftward counterparts, they just assign the value in an opposite direction.

Overwhelmed yet? Don’t be. This is just meant to show you that there are options and you will likely come across them sooner or later. My suggestion is to stick with the tried and true <- operator. This is the most conventional assignment operator used and is what you will find in all the base R source code…which means it should be good enough for you.

We can then evaluate the variable by simply typing x at the command line which will return the value of x. Note that prior to the value returned you’ll see ## [1] in the command line. This simply implies that the output returned is the first output. Note that you can type any comments in your code by preceding the comment with the hash tag (#) symbol. Any values, symbols, and texts following # will not be evaluated.

# evaluation

x

## [1] 3

Lastly, note that R is a case sensitive programming language. Meaning all variables, functions, and objects must be called by their exact spelling:

x <- 1

y <- 3

z <- 4

x * y * z

## [1] 12

x * Y * z

## Error in eval(expr, envir, enclos): object 'Y' not found

x (note how this shows up in your Global Environment).y.x and y at the command line.rm() function to remove these objects from you working environment.At its most basic function R can be used as a calculator. When applying basic arithmetic, the PEMDAS order of operations applies: parentheses first followed by exponentiation, multiplication and division, and final addition and subtraction.

8 + 9 / 5 ^ 2

## [1] 8.36

8 + 9 / (5 ^ 2)

## [1] 8.36

8 + (9 / 5) ^ 2

## [1] 11.24

(8 + 9) / 5 ^ 2

## [1] 0.68

By default R will display seven digits but this can be changed using options() as previously outlined.

1 / 7

## [1] 0.1428571

options(digits = 3)

1 / 7

## [1] 0.143

Also, large numbers will be expressed in scientific notation which can also be adjusted using options().

888888 * 888888

## [1] 7.9e+11

options(digits = 10)

888888 * 888888

## [1] 790121876544

Note that the largest number of digits that can be displayed is 22. Requesting any larger number of digits will result in an error message.

pi

## [1] 3.141592654

options(digits = 22)

pi

## [1] 3.141592653589793115998

options(digits = 23)

## Error in options(digits = 23): invalid 'digits' parameter, allowed 0...22

pi

## [1] 3.141592653589793115998

We can also perform integer divide (%/%) and modulo (%%) functions. The integer divide function will give the integer part of a fraction while the modulo will provide the remainder.

42 / 4 # regular division

## [1] 10.5

42 %/% 4 # integer division

## [1] 10

42 %% 4 # modulo (remainder)

## [1] 2

There are many built-in functions to be aware of. These include but are not limited to the following. Go ahead and run this code in your console.

x <- 10

abs(x) # absolute value

sqrt(x) # square root

exp(x) # exponential transformation

log(x) # logarithmic transformation

cos(x) # cosine and other trigonometric functions

When performing undefined calculations, R will produce Inf (infinity) and NaN (not a number) outputs.

1 / 0 # infinity

## [1] Inf

Inf - Inf # infinity minus infinity

## [1] NaN

-1 / 0 # negative infinity

## [1] -Inf

0 / 0 # not a number

## [1] NaN

sqrt(-9) # square root of -9

## Warning in sqrt(-9): NaNs produced

## [1] NaN

D, K, and h respectively.Q. (hint: you’ll probably need the sqrt() function in R)A key difference between R and many other languages is a topic known as vectorization. What does this mean? It means that many functions that are to be applied individually to each element in a vector of numbers require a loop assessment to evaluate; however, in R many of these functions have been coded in C to perform much faster than a for loop would perform. For example, let’s say you want to add the elements of two separate vectors of numbers (x and y).

x <- c(1, 3, 4)

y <- c(1, 2, 4)

x

## [1] 1 3 4

y

## [1] 1 2 4

In other languages you might have to run a loop to add two vectors together. In this for loop I print each iteration to show that the loop calculates the sum for the first elements in each vector, then performs the sum for the second elements, etc.

# empty vector

z <- as.vector(NULL)

# `for` loop to add corresponding elements in each vector

for (i in seq_along(x)) {

z[i] <- x[i] + y[i]

print(z)

}

## [1] 2

## [1] 2 5

## [1] 2 5 8

Instead, in R, + is a vectorized function which can operate on entire vectors at once. So rather than creating for loops for many functions, you can just use simple syntax:

# add each element in x and y

x + y

## [1] 2 5 8

# multiply each element in x and y

x * y

## [1] 1 6 16

# compare each element in x to y

x > y

## [1] FALSE TRUE FALSE

When performing vector operations in R, it is important to know about recycling. When performing an operation on two or more vectors of unequal length, R will recycle elements of the shorter vector(s) to match the longest vector. For example:

long <- 1:10

short <- 1:5

long

## [1] 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

short

## [1] 1 2 3 4 5

long + short

## [1] 2 4 6 8 10 7 9 11 13 15

The elements of long and short are added together starting from the first element of both vectors. When R reaches the end of the short vector, it starts again at the first element of short and continues until it reaches the last element of the long vector. This functionality is very useful when you want to perform the same operation on every element of a vector. For example, say we want to multiply every element of our vector long by 3:

long <- 1:10

c <- 3

long * c

## [1] 3 6 9 12 15 18 21 24 27 30

There are no scalars in R, so c is actually a vector of length 1; in order to add its value to every element of long, it is recycled to match the length of long.

When the length of the longer object is a multiple of the shorter object length, the recycling occurs silently. When the longer object length is not a multiple of the shorter object length, a warning is given:

even_length <- 1:10

odd_length <- 1:3

even_length + odd_length

## Warning in even_length + odd_length: longer object length is not a multiple

## of shorter object length

## [1] 2 4 6 5 7 9 8 10 12 11

my_vec <- 1:10.my_vec.my_vec by 2.my_vec2 <- 10:18 and add my_vec to my_vec2.“Good coding style is like using correct punctuation. You can manage without it, but it sure makes things easier to read.” - Hadley Wickham

As a medium of communication, its important to realize that the readability of code does in fact make a difference. Well styled code has many benefits to include making it easy to i) read, ii) extend, and iii) debug. Unfortunately, R does not come with official guidelines for code styling but such is an inconvenient truth of most open source software. However, this should not lead you to believe there is no style to be followed and over time implicit guidelines for proper code styling have been documented. What follows are guidelines that have been widely accepted as good practice in the R community and are based on Google’s and Hadley Wickham’s R style guides.

File names should be meaningful and end with a .R extension.

# Good

weather-analysis.R

emerson-text-analysis.R

# Bad

basic-stuff.r

detail.r

If files need to be run in sequence, prefix them with numbers:

0-download.R

1-preprocessing.R

2-explore.R

3-fit-model.R

In R, naming conventions for variables and functions are famously muddled. They include the following:

namingconvention # all lower case; no separator

naming.convention # period separator

naming_convention # underscore separator

namingConvention # lower camel case

NamingConvention # upper camel case

Historically, there has been no clearly preferred approach with multiple naming styles sometimes used within a single package. Bottom line, your naming convention will be driven by your preference but the ultimate goal should be consistency.

My personal preference is to use all lowercase with an underscore (_) to separate words within a name. This follows Hadley Wickham’s suggestions in his style guide. Furthermore, variable names should be nouns and function names should be verbs to help distinguish their purpose. Also, refrain from using existing names of functions (i.e. mean, sum, true).

Organization of your code is also important. There’s nothing like trying to decipher 2,000 lines of code that has no organization. The easiest way to achieve organization is to comment your code. The general commenting scheme I use is the following.

I break up principal sections of my code that have a common purpose with:

#################

# Download Data #

#################

lines of code here

###################

# Preprocess Data #

###################

lines of code here

########################

# Exploratory Analysis #

########################

lines of code here

Then comments for specific lines of code can be done as follows:

code_1 # short comments can be placed to the right of code

code_2 # blah

code_3 # blah

# or comments can be placed above a line of code

code_4

# Or extremely long lines of commentary that go beyond the suggested 80

# characters per line can be broken up into multiple lines. Just don't forget

# to use the hash on each.

code_5

The maximum number of characters on a single line of code should be 80 or less. If you are using RStudio you can have a margin displayed so you know when you need to break to a new line.2 This allows your code to be printed on a normal 8.5 x 11 page with a reasonably sized font. Also, when indenting your code use two spaces rather than using tabs. The only exception is if a line break occurs inside parentheses. In this case align the wrapped line with the first character inside the parenthesis:

super_long_name <- seq(ymd_hm("2015-1-1 0:00"),

ymd_hm("2015-1-1 12:00"),

by = "hour")

Proper spacing within your code also helps with readability. The following pulls straight from Hadley Wickham’s suggestions. Place spaces around all infix operators (=, +, -, <-, etc.). The same rule applies when using = in function calls. Always put a space after a comma, and never before.

# Good

average <- mean(feet / 12 + inches, na.rm = TRUE)

# Bad

average<-mean(feet/12+inches,na.rm=TRUE)

There’s a small exception to this rule: :, :: and ::: don’t need spaces around them.

# Good

x <- 1:10

base::get

# Bad

x <- 1 : 10

base :: get

It is important to think about style when communicating any form of language. Writing code is no exception and is especially important if your code will be read by others. Following these basic style guides will get you on the right track for writing code that can be easily communicated to others.

Go back through the script you’ve been writing to execute the exercises in this tutorial and make sure

Go to RStudio on the menu bar then Preferences > Code > Display and you can select the “show margin” option and set the margin to 80. ↩