Vast amount of information exists across the interminable webpages that exist online. Much of this information are “unstructured” text that may be useful in our analyses. This section covers the basics of scraping these texts from online sources. Throughout this section I will illustrate how to extract different text components of webpages by dissecting the Wikipedia page on web scraping. However, its important to first cover one of the basic components of HTML elements as we will leverage this information to pull desired information. I offer only enough insight required to begin scraping; I highly recommend XML and Web Technologies for Data Sciences with R and Automated Data Collection with R to learn more about HTML and XML element structures.

HTML elements are written with a start tag, an end tag, and with the content in between: <tagname>content</tagname>. The tags which typically contain the textual content we wish to scrape, and the tags we will leverage in the next two sections, include:

<h1>, <h2>,…,<h6>: Largest heading, second largest heading, etc.<p>: Paragraph elements<ul>: Unordered bulleted list<ol>: Ordered list<li>: Individual List item<div>: Division or section<table>: TableFor example, text in paragraph form that you see online is wrapped with the HTML paragraph tag <p> as in:

<p>

This paragraph represents

a typical text paragraph

in HTML form

</p>

It is through these tags that we can start to extract textual components (also referred to as nodes) of HTML webpages.

To scrape online text we’ll make use of the relatively newer rvest package. rvest was created by the RStudio team inspired by libraries such as beautiful soup which has greatly simplified web scraping. rvest provides multiple functionalities; however, in this section we will focus only on extracting HTML text with rvest. Its important to note that rvest makes use of of the pipe operator (%>%) developed through the magrittr package. If you are not familiar with the functionality of %>% I recommend you jump to the section on Simplifying Your Code with %>% so that you have a better understanding of what’s going on with the code.

To extract text from a webpage of interest, we specify what HTML elements we want to select by using html_nodes(). For instance, if we want to scrape the primary heading for the Web Scraping Wikipedia webpage we simply identify the <h1> node as the node we want to select. html_nodes() will identify all <h1> nodes on the webpage and return the HTML element. In our example we see there is only one <h1> node on this webpage.

library(rvest)

scraping_wiki <- read_html("https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Web_scraping")

scraping_wiki %>%

html_nodes("h1")

## {xml_nodeset (1)}

## [1] <h1 id="firstHeading" class="firstHeading" lang="en">Web scraping</h1>

To extract only the heading text for this <h1> node, and not include all the HTML syntax we use html_text() which returns the heading text we see at the top of the Web Scraping Wikipedia page.

scraping_wiki %>%

html_nodes("h1") %>%

html_text()

## [1] "Web scraping"

If we want to identify all the second level headings on the webpage we follow the same process but instead select the <h2> nodes. In this example we see there are 10 second level headings on the Web Scraping Wikipedia page.

scraping_wiki %>%

html_nodes("h2") %>%

html_text()

## [1] "Contents"

## [2] "Techniques[edit]"

## [3] "Legal issues[edit]"

## [4] "Notable tools[edit]"

## [5] "See also[edit]"

## [6] "Technical measures to stop bots[edit]"

## [7] "Articles[edit]"

## [8] "References[edit]"

## [9] "See also[edit]"

## [10] "Navigation menu"

Next, we can move on to extracting much of the text on this webpage which is in paragraph form. We can follow the same process illustrated above but instead we’ll select all <p> nodes. This selects the 17 paragraph elements from the web page; which we can examine by subsetting the list p_nodes to see the first line of each paragraph along with the HTML syntax. Just as before, to extract the text from these nodes and coerce them to a character string we simply apply html_text().

p_nodes <- scraping_wiki %>%

html_nodes("p")

length(p_nodes)

## [1] 17

p_nodes[1:6]

## {xml_nodeset (6)}

## [1] <p><b>Web scraping</b> (<b>web harvesting</b> or <b>web data extract ...

## [2] <p>Web scraping is closely related to <a href="/wiki/Web_indexing" t ...

## [3] <p/>

## [4] <p/>

## [5] <p>Web scraping is the process of automatically collecting informati ...

## [6] <p>Web scraping may be against the <a href="/wiki/Terms_of_use" titl ...

p_text <- scraping_wiki %>%

html_nodes("p") %>%

html_text()

p_text[1]

## [1] "Web scraping (web harvesting or web data extraction) is a computer software technique of extracting information from websites. Usually, such software programs simulate human exploration of the World Wide Web by either implementing low-level Hypertext Transfer Protocol (HTTP), or embedding a fully-fledged web browser, such as Mozilla Firefox."

Not too bad; however, we may not have captured all the text that we were hoping for. Since we extracted text for all <p> nodes, we collected all identified paragraph text; however, this does not capture the text in the bulleted lists. For example, when you look at the Web Scraping Wikipedia page you will notice a significant amount of text in bulleted list format following the third paragraph under the Techniques heading. If we look at our data we’ll see that that the text in this list format are not capture between the two paragraphs:

p_text[5]

## [1] "Web scraping is the process of automatically collecting information from the World Wide Web. It is a field with active developments sharing a common goal with the semantic web vision, an ambitious initiative that still requires breakthroughs in text processing, semantic understanding, artificial intelligence and human-computer interactions. Current web scraping solutions range from the ad-hoc, requiring human effort, to fully automated systems that are able to convert entire web sites into structured information, with limitations."

p_text[6]

## [1] "Web scraping may be against the terms of use of some websites. The enforceability of these terms is unclear.[4] While outright duplication of original expression will in many cases be illegal, in the United States the courts ruled in Feist Publications v. Rural Telephone Service that duplication of facts is allowable. U.S. courts have acknowledged that users of \"scrapers\" or \"robots\" may be held liable for committing trespass to chattels,[5][6] which involves a computer system itself being considered personal property upon which the user of a scraper is trespassing. The best known of these cases, eBay v. Bidder's Edge, resulted in an injunction ordering Bidder's Edge to stop accessing, collecting, and indexing auctions from the eBay web site. This case involved automatic placing of bids, known as auction sniping. However, in order to succeed on a claim of trespass to chattels, the plaintiff must demonstrate that the defendant intentionally and without authorization interfered with the plaintiff's possessory interest in the computer system and that the defendant's unauthorized use caused damage to the plaintiff. Not all cases of web spidering brought before the courts have been considered trespass to chattels.[7]"

This is because the text in this list format are contained in <ul> nodes. To capture the text in lists, we can use the same steps as above but we select specific nodes which represent HTML lists components. We can approach extracting list text two ways.

First, we can pull all list elements (<ul>). When scraping all <ul> text, the resulting data structure will be a character string vector with each element representing a single list consisting of all list items in that list. In our running example there are 21 list elements as shown in the example that follows. You can see the first list scraped is the table of contents and the second list scraped is the list in the Techniques section.

ul_text <- scraping_wiki %>%

html_nodes("ul") %>%

html_text()

length(ul_text)

## [1] 21

ul_text[1]

## [1] "\n1 Techniques\n2 Legal issues\n3 Notable tools\n4 See also\n5 Technical measures to stop bots\n6 Articles\n7 References\n8 See also\n"

# read the first 200 characters of the second list

substr(ul_text[2], start = 1, stop = 200)

## [1] "\nHuman copy-and-paste: Sometimes even the best web-scraping technology cannot replace a human’s manual examination and copy-and-paste, and sometimes this may be the only workable solution when the web"

An alternative approach is to pull all <li> nodes. This will pull the text contained in each list item for all the lists. In our running example there’s 146 list items that we can extract from this Wikipedia page. The first eight list items are the list of contents we see towards the top of the page. List items 9-17 are the list elements contained in the “Techniques” section, list items 18-44 are the items listed under the “Notable Tools” section, and so on.

li_text <- scraping_wiki %>%

html_nodes("li") %>%

html_text()

length(li_text)

## [1] 147

li_text[1:8]

## [1] "1 Techniques" "2 Legal issues"

## [3] "3 Notable tools" "4 See also"

## [5] "5 Technical measures to stop bots" "6 Articles"

## [7] "7 References" "8 See also"

At this point we may believe we have all the text desired and proceed with joining the paragraph (p_text) and list (ul_text or li_text) character strings and then perform the desired textual analysis. However, we may now have captured more text than we were hoping for. For example, by scraping all lists we are also capturing the listed links in the left margin of the webpage. If we look at the 104-136 list items that we scraped, we’ll see that these texts correspond to the left margin text.

li_text[104:136]

## [1] "Main page" "Contents" "Featured content"

## [4] "Current events" "Random article" "Donate to Wikipedia"

## [7] "Wikipedia store" "Help" "About Wikipedia"

## [10] "Community portal" "Recent changes" "Contact page"

## [13] "What links here" "Related changes" "Upload file"

## [16] "Special pages" "Permanent link" "Page information"

## [19] "Wikidata item" "Cite this page" "Create a book"

## [22] "Download as PDF" "Printable version" "Català"

## [25] "Deutsch" "Español" "Français"

## [28] "Íslenska" "Italiano" "Latviešu"

## [31] "Nederlands" "日本語" "Српски / srpski"

If we desire to scrape every piece of text on the webpage than this won’t be of concern. In fact, if we want to scrape all the text regardless of the content they represent there is an easier approach. We can capture all the content to include text in paragraph (<p>), lists (<ul>, <ol>, and <li>), and even data in tables (<table>) by using <div>. This is because these other elements are usually a subsidiary of an HTML division or section so pulling all <div> nodes will extract all text contained in that division or section regardless if it is also contained in a paragraph or list.

all_text <- scraping_wiki %>%

html_nodes("div") %>%

html_text()

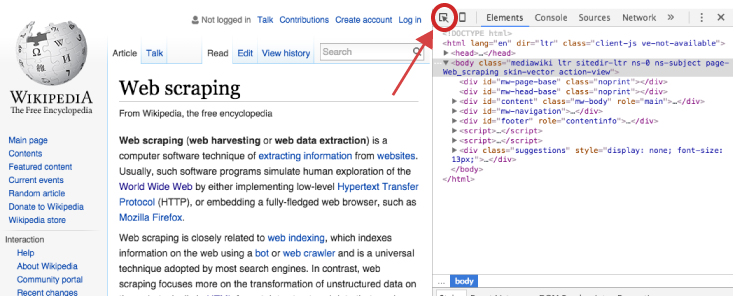

However, if we are concerned only with specific content on the webpage then we need to make our HTML node selection process a little more focused. To do this we, we can use our browser’s developer tools to examine the webpage we are scraping and get more details on specific nodes of interest. If you are using Chrome or Firefox you can open the developer tools by clicking F12 (Cmd + Opt + I for Mac) or for Safari you would use Command-Option-I. An additional option which is recommended by Hadley Wickham is to use selectorgadget.com, a Chrome extension, to help identify the web page elements you need1.

Once the developer’s tools are opened your primary concern is with the element selector. This is located in the top lefthand corner of the developers tools window.

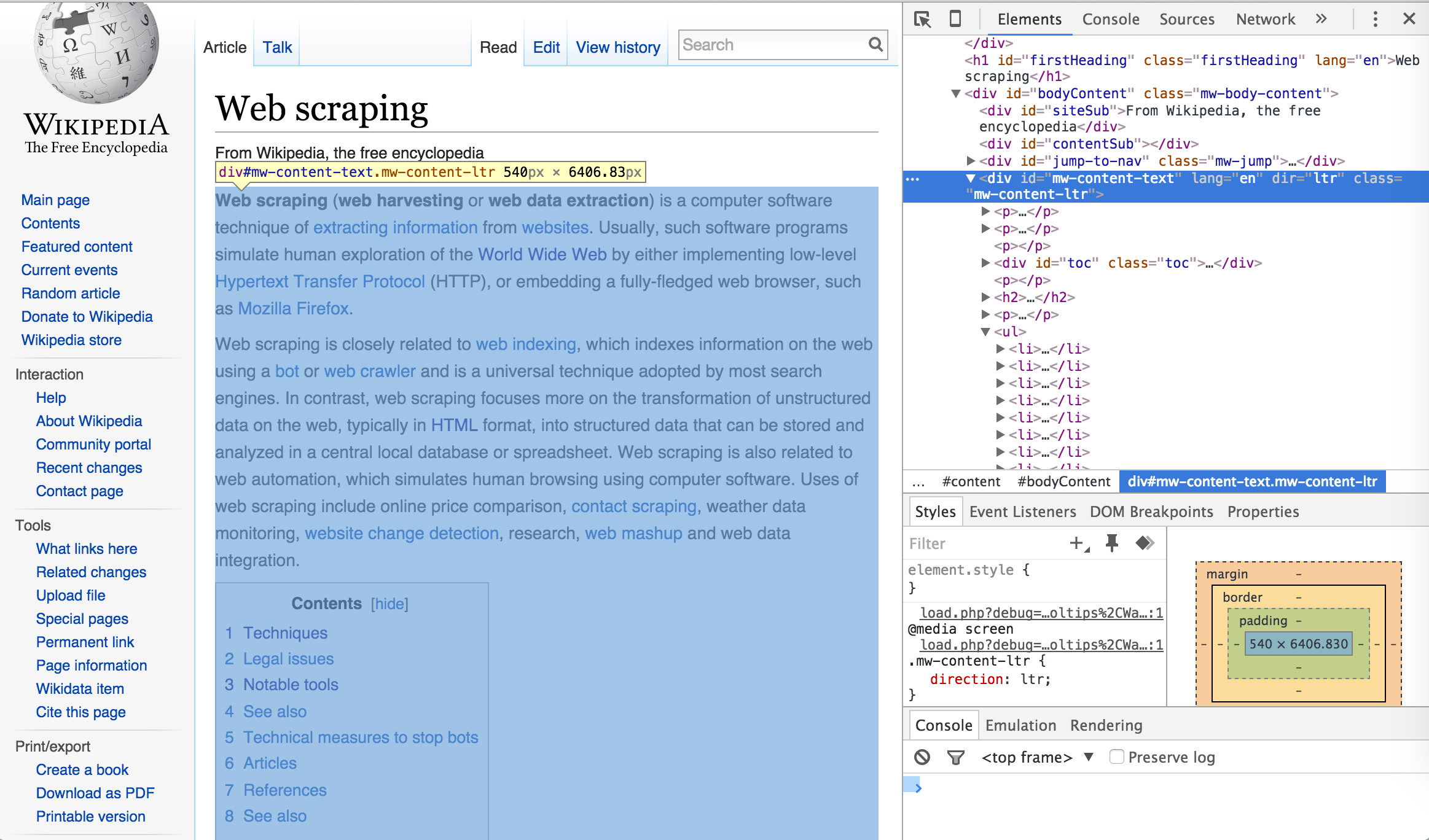

Once you’ve selected the element selector you can now scroll over the elements of the webpage which will cause each element you scroll over to be highlighted. Once you’ve identified the element you want to focus on, select it. This will cause the element to be identified in the developer tools window. For example, if I am only interested in the main body of the Web Scraping content on the Wikipedia page then I would select the element that highlights the entire center component of the webpage. This highlights the corresponding element <div id="bodyContent" class="mw-body-content"> in the developer tools window as the following illustrates.

I can now use this information to select and scrape all the text from this specific <div> node by calling the ID name (“#mw-content-text”) in html_nodes()2. As you can see below, the text that is scraped begins with the first line in the main body of the Web Scraping content and ends with the text in the See Also section which is the last bit of text directly pertaining to Web Scraping on the webpage. Explicitly, we have pulled the specific text associated with the web content we desire.

body_text <- scraping_wiki %>%

html_nodes("#mw-content-text") %>%

html_text()

# read the first 207 characters

substr(body_text, start = 1, stop = 207)

## [1] "Web scraping (web harvesting or web data extraction) is a computer software technique of extracting information from websites. Usually, such software programs simulate human exploration of the World Wide Web"

# read the last 73 characters

substr(body_text, start = nchar(body_text)-73, stop = nchar(body_text))

## [1] "See also[edit]\n\nData scraping\nData wrangling\nKnowledge extraction\n\n\n\n\n\n\n\n\n"

Using the developer tools approach allows us to be as specific as we desire. We can identify the class name for a specific HTML element and scrape the text for only that node rather than all the other elements with similar tags. This allows us to scrape the main body of content as we just illustrated or we can also identify specific headings, paragraphs, lists, and list components if we desire to scrape only these specific pieces of text:

# Scraping a specific heading

scraping_wiki %>%

html_nodes("#Techniques") %>%

html_text()

## [1] "Techniques"

# Scraping a specific paragraph

scraping_wiki %>%

html_nodes("#mw-content-text > p:nth-child(20)") %>%

html_text()

## [1] "In Australia, the Spam Act 2003 outlaws some forms of web harvesting, although this only applies to email addresses.[20][21]"

# Scraping a specific list

scraping_wiki %>%

html_nodes("#mw-content-text > div:nth-child(22)") %>%

html_text()

## [1] "\n\nApache Camel\nArchive.is\nAutomation Anywhere\nConvertigo\ncURL\nData Toolbar\nDiffbot\nFirebug\nGreasemonkey\nHeritrix\nHtmlUnit\nHTTrack\niMacros\nImport.io\nJaxer\nNode.js\nnokogiri\nPhantomJS\nScraperWiki\nScrapy\nSelenium\nSimpleTest\nwatir\nWget\nWireshark\nWSO2 Mashup Server\nYahoo! Query Language (YQL)\n\n"

# Scraping a specific reference list item

scraping_wiki %>%

html_nodes("#cite_note-22") %>%

html_text()

## [1] "^ \"Web Scraping: Everything You Wanted to Know (but were afraid to ask)\". Distil Networks. 2015-07-22. Retrieved 2015-11-04. "

With any webscraping activity, especially involving text, there is likely to be some clean up involved. For example, in the previous example we saw that we can specifically pull the list of Notable Tools; however, you can see that in between each list item rather than a space there contains one or more \n which is used in HTML to specify a new line. We can clean this up quickly with a little character string manipulation.

library(magrittr)

scraping_wiki %>%

html_nodes("#mw-content-text > div:nth-child(22)") %>%

html_text()

## [1] "\n\nApache Camel\nArchive.is\nAutomation Anywhere\nConvertigo\ncURL\nData Toolbar\nDiffbot\nFirebug\nGreasemonkey\nHeritrix\nHtmlUnit\nHTTrack\niMacros\nImport.io\nJaxer\nNode.js\nnokogiri\nPhantomJS\nScraperWiki\nScrapy\nSelenium\nSimpleTest\nwatir\nWget\nWireshark\nWSO2 Mashup Server\nYahoo! Query Language (YQL)\n\n"

scraping_wiki %>%

html_nodes("#mw-content-text > div:nth-child(22)") %>%

html_text() %>%

strsplit(split = "\n") %>%

unlist() %>%

.[. != ""]

## [1] "Apache Camel" "Archive.is"

## [3] "Automation Anywhere" "Convertigo"

## [5] "cURL" "Data Toolbar"

## [7] "Diffbot" "Firebug"

## [9] "Greasemonkey" "Heritrix"

## [11] "HtmlUnit" "HTTrack"

## [13] "iMacros" "Import.io"

## [15] "Jaxer" "Node.js"

## [17] "nokogiri" "PhantomJS"

## [19] "ScraperWiki" "Scrapy"

## [21] "Selenium" "SimpleTest"

## [23] "watir" "Wget"

## [25] "Wireshark" "WSO2 Mashup Server"

## [27] "Yahoo! Query Language (YQL)"

Similarly, as we saw in our example above with scraping the main body content (body_text), there are extra characters (i.e. \n, \, ^) in the text that we may not want. Using a little regex we can clean this up so that our character string consists of only text that we see on the screen and no additional HTML code embedded throughout the text.

library(stringr)

# read the last 700 characters

substr(body_text, start = nchar(body_text)-700, stop = nchar(body_text))

## [1] " 2010). \"Intellectual Property: Website Terms of Use\". Issue 26: June 2010. LK Shields Solicitors Update. p. 03. Retrieved 2012-04-19. \n^ National Office for the Information Economy (February 2004). \"Spam Act 2003: An overview for business\" (PDF). Australian Communications Authority. p. 6. Retrieved 2009-03-09. \n^ National Office for the Information Economy (February 2004). \"Spam Act 2003: A practical guide for business\" (PDF). Australian Communications Authority. p. 20. Retrieved 2009-03-09. \n^ \"Web Scraping: Everything You Wanted to Know (but were afraid to ask)\". Distil Networks. 2015-07-22. Retrieved 2015-11-04. \n\n\nSee also[edit]\n\nData scraping\nData wrangling\nKnowledge extraction\n\n\n\n\n\n\n\n\n"

# clean up text

body_text %>%

str_replace_all(pattern = "\n", replacement = " ") %>%

str_replace_all(pattern = "[\\^]", replacement = " ") %>%

str_replace_all(pattern = "\"", replacement = " ") %>%

str_replace_all(pattern = "\\s+", replacement = " ") %>%

str_trim(side = "both") %>%

substr(start = nchar(body_text)-700, stop = nchar(body_text))

## [1] "012-04-19. National Office for the Information Economy (February 2004). Spam Act 2003: An overview for business (PDF). Australian Communications Authority. p. 6. Retrieved 2009-03-09. National Office for the Information Economy (February 2004). Spam Act 2003: A practical guide for business (PDF). Australian Communications Authority. p. 20. Retrieved 2009-03-09. Web Scraping: Everything You Wanted to Know (but were afraid to ask) . Distil Networks. 2015-07-22. Retrieved 2015-11-04. See also[edit] Data scraping Data wrangling Knowledge extraction"

So there we have it, text scraping in a nutshell. Although not all encompassing, this section covered the basics of scraping text from HTML documents. Whether you want to scrape text from all common text-containing nodes such as <div>, <p>, <ul> and the like or you want to scrape from a specific node using the specific ID, this section provides you the basic fundamentals of using rvest to scrape the text you need. In the next section we move on to scraping data from HTML tables.

You can learn more about selectors at flukeout.github.io ↩

You can simply assess the name of the ID in the highlighted element or you can right click the highlighted element in the developer tools window and select Copy selector. You can then paste directly into html_nodes() as it will paste the exact ID name that you need for that element. ↩